River disputes

River disputes

Why in news?

Delhi Chief Minister and Aam Aadmi Party convener Arvind Kejriwal urged Prime Minister Narendra Modi to solve the long-pending Sutlej-Yamuna Link Canal issue between Punjab and Haryana, saying, “It’s the duty of the Centre to ensure water for Punjab and Haryana, not to make them fight

Accusation against central government

- Many states like Tamil Nadu, Kerala, and Karnataka have complained of inadequate disbursal of funds by Centre, claiming that the delay has caused stalling of important dam projects.

- Moreover, States have often accused the Centre of hogging the credit for several such developments achieved by State governments in their area.

Why there is a conflict?

- Subjects like electricity, water resources, law and order, judiciary, and finance have a power overlap between Centre and States in the Constitution – leading to a tussle between the Centre and States.

Centre-State power struggle over India’s waters

Water: Union List vs State List

- Article 246 grants the Centre the exclusive power to make laws on the following subjects under List I of the Seventh Schedule:

- Decide on shipping and navigation on inland and tidal (sea) waterways and on national waterways for vessels

- Regulate training and education of mercantile marines by states and other agencies

- Decide on goods, passengers by sea or national waterways via mechanically propelled vessels

- Regulate and develop interstate rivers and river valleys

- Decide on fishing and fisheries beyond territorial waters

Similarly, States are empowered to:

- Develop roads, bridges, ferries, municipal tramways, ropeways and other means of communication on inland waterways in the State

- Decide on water supply, irrigation and canals, drainage and embankments, water storage and water power

- Taxes on goods and passengers carried by road or on inland waterways

- Decide on shipping and navigation on inland waterways via mechanically propelled vessels and carriage of passengers and goods on such waters

On comparing the two lists, there appears to be an overlap in the powers of the Centre and State as far asshipping and navigation on inland waterways is concerned. Moreover, the development of water supplies, canals and riverbanks is also an area of conflict between States.

Centre and inter-State river disputes

- One of the major water-related issues tasked to the Centre, inter-State river disputes in India are governed bythe Inter-State River Water Dispute Act, 1956. An amendment to the Act was passed by the Lok Sabha in 2019 but is yet to get the Upper House’s nod.

How are river disputes resolved?

- Under the Act, any State may request the Centre to refer an inter-State river dispute to a tribunal for adjudication. If the Centre feels that negotiations cannot settle the dispute, it may setup such a Water Disputes Tribunal within one year of the complaint. The tribunal must decide on the dispute within three years, which may be extended by two years.

- However, if the matter is again referred to the Tribunal for further consideration, it must submit a report to the Centre within one year, which may be extended if deemed necessary. All decisions of the Tribunal are final and binding.

- The Centre may create a scheme to give effect to the decision of such a tribunal. It is also tasked with maintaining a data bank of each river basin in the country.

- Disputes unresolved by the committee will be sent to the Tribunal which comprises of Central government ministers or nominees and a Supreme Court Judge. The Tribunal must decide on any dispute within one year and its decision will be final and binding on the parties involved. Also, the Centre is mandated to create a scheme to implement the Tribunal’s decision.

Which are India’s major river disputes?

- Cauvery dispute (Karnataka-Tamil Nadu): India’s southern states Karnataka and Tamil Nadu have been feuding over the water usage of the Cauvery River since 1924. During the British era, as per an agreement between the Madras Presidency and Mysore state, Tamil Nadu and Puducherry were awarded 75% of surplus water, while Karnataka would get 23% and the remaining would be used by Kerala.

- Finally, in February 2018, the apex court reduced Tamil Nadu’s allocation to 177.25 TMC from 192 TMC, hiking Karnataka’s allocation by 14.75 TMC. With the dispute resolved, the Tribunal was dissolved and both states are complying with the award. On September 19, 2022, Karnataka released 425 TMC to Tamil Nadu as opposed to its allocation of 177.25 TMC due to excess water flow.

- Sutlej-Yamuna Link Canal (Punjab-Haryana): After the partition of Punjab in 1947, the rivers – Ravi and Beas which had a combined flow of 15.85 MAF (million acre feet) — was split as such – Rajasthan (8 MAF), undivided Punjab (7.2 MAF) and Jammu and Kashmir (0.65 MAF) respectively. After the 1966 reorganisation of Punjab resulted in the creation of Haryana, the new state was allocated 3.5 MAF per year; however Punjab sought to retain its share of 7.2 MAF (the volume allotted to undivided Punjab). After reassessment in 1981, Punjab was allotted 4.22 MAF, Haryana 3.5 MAF and Rajasthan 8.6 MAF. To implement this decision, the 214 km-long Sutlej-Yamuna Link (SYL) Canal was flagged in 1982 with 122 km to be constructed in Punjab and 92 km in Harayana.

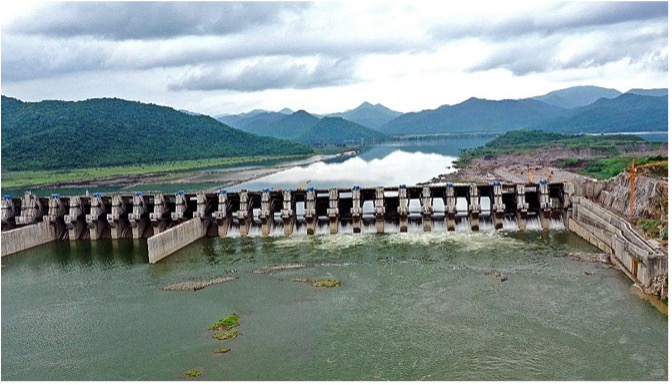

- Polavaram project dispute (Andhra Pradesh-Telangana): The Polavaram project was constructed in undivided Andhra Pradesh to direct 80 TMC of Godavari river waters to the Krishna river to share water with Karnataka and Maharashtra. Since the formation of Telangana in 2014, the project has been a bone of contention between the two States. While Andhra Pradesh has claimed the project is essential to irrigate its Godavari districts, Telangana has raised fears of backwaters flooding theKhammam district.

Apart from resolving water disputes, the Centre has also listed 111 inland rivers as National Waterways in The National Waterways Bill, 2015, empowering it to create laws on shipping and travel on the listed waterways.

State-level water issues

- On a State level, each government forms laws for water management across its districts to regulate water usage by industries, set rules for water treatment, set water tariffs and manage sewage water generated. The Haryana Water Resources (Conservation, Regulation and Management) Authority Act, 2020 is the example of such an act which constitutes an authority to fix tariffs for all uses of water and set rules for the use & disposal of treated wastewater.

- Similarly, the Karnataka government passed the Bangalore Water Supply and Sewerage Act, 2021 to provide rainwater harvesting structures to citizens, so as to reduce dependency on Cauvery or underground water, and also mitigate urban flooding. Some states like Andhra Pradesh and Kerala have passed irrigation and water conservation laws to stop river pollution, specify limits on water supply for irrigating crops and penalize those who violate these norms.

- Though States manage rivers and prevent its pollution, the Centre also undertakes river-cleaning projects of India’s major rivers – like the National Mission for Clean Ganga (NMCG). Under the Environment (Protection) Amendment Act (EPA), 2016, the NMCG was given a two tier management structure — Governing Council and Executive Committee — at National, State and district levels.

Local-level: Drinking water supply

- On a local level, providing tapped water to all rural and urban households falls under the purview of the various civic bodies managed by the state governments. The right to clean drinking water has been read into the right to life under Article 21 of the constitution. Water has been deemed a fundamental resource and the Centre and States have been tasked to make policies to distribute water among people.

- The Centre’s Jal Jeevan Mission (JJM) aims to provide a Functional Household Tap Connection (FHTC) to every rural household by 2024, in collaboration with States and Union Territories (UTs). The scheme also aims to develop bulk water transfer facilities, treatment plants and a robust in-village water distribution network. With an outlay of Rs 3.60 lakh crore, the Centre has pledged a contribution of 100% funds for UTs without a legislature, 90% for North Eastern and Himalayan States/UTs and 50% for other states.