Published on: January 28, 2023

Indus Waters Treaty

Indus Waters Treaty

Why in news? India announced that it wants to modify the 62-year-old Indus Waters Treaty (IWT) with Pakistan, citing as Pakistan’s refusal to resolve disputes over the Kishenganga and Ratle hydropower projects.

Highlights:

- India protested Pakistan’s “unilateral” decision to approach a court of arbitration at Hague with India boycotting the court process.

- The decision to issue notice to Pakistan, with a request for a response within 90 days, is a major step and could lead to the unravelling and renegotiation of the water-sharing treaty

History of the treaty

- In 1960, India and Pakistan signed the Indus Waters Treaty with the World Bank as a signatory of the pact.

What are the provisions under the treaty?

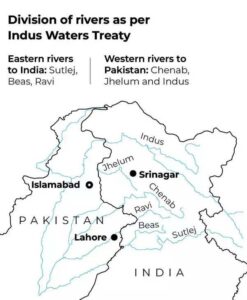

- India has an absolute control of all the waters of eastern rivers of the Indus — Ravi, Sutlej and Beas.

- Pakistan shall receive for unrestricted use all those waters of the western rivers — the Indus, Jhelum and Chenab — which India is under obligation to let flow beyond the permitted uses.

- All the waters of the eastern rivers with average annual flow of around 33 million acre feet (MAF) are allocated to India for unrestricted use, while the waters of western rivers with average annual flow of around 135 MAF is allocated largely to Pakistan.

- India is permitted to use the waters of the western rivers for domestic use, non-consumptive use, agricultural and generation of hydro-electric power.

- The right to generate hydroelectricity from the western rivers is unrestricted subject to the conditions for design and operation of the treaty.

- India can also create storages up to 3.6 MAF on the western rivers.

- Enables India and Pakistan to establish a permanent post of Commissioner for Indus Waters. The two commissioners constitute the Permanent Indus Commission (PIC).

- Unless either government should decide to take up any particular issue directly with the other, each commissioner will be the representative of his government for all matters arising out of this treaty.

- According to Pakistan, the Court of Arbitration had been set up “under the relevant provisions of the IWT

What is point of contention ?

- Construction on the 330 MW Kishanganga hydroelectric project built on the tributaries of the Indus began in 2007.

- Meanwhile, the foundation stone for the Ratle Hydroelectric Plant to be constructed on the Chenab was laid in 2013.

- Pakistan raised a dispute on the two projects, saying it violated the Indus Waters Treaty (IWT) by criticising the Kishanganga project , as it blocks water that flows into Pakistan.

- In 2015, Pakistan approached the World Bank and sought the appointment of a neutral expert to address its objections to the Kishanganga and Ratle Hydro Electric Projects.

- In 2017, the World Bank said India is allowed to construct hydroelectric power facilities on tributaries of the Jhelum and Chenab rivers with certain restrictions under the 1960 treaty.

What is the dispute resolution process?

- According to treaty that deals with the “Settlement of Differences and Disputes”, there are three possible steps to decide on objections raised by either side:

- Working within the “Permanent Indus Commission” (PIC) of the Indian and Pakistani delegation of water experts that meet regularly

- Consulting a World Bank-appointed neutral expert

- Setting up a court process to adjudicate the case through the World Bank and the Permanent Court of Arbitrage (PCA).

Neutral expert vs courts of arbitration

- Article IX of the IWT makes a distinction between “differences” and “disputes”.

- It states that if the Permanent Indus Commission, a bilateral commission consisting of officials from India and Pakistan, cannot come to an agreement on an issue, then it is deemed a “difference”.

- If this difference falls under provisions of Part 1 of Annexure F1, a neutral expert is allowed to intervene.

- There are 23 provisions under Part 1 of Annexure F1 that deal with a variety of issues ranging from questions about the boundary of the drainage basins to any new hydroelectric plants on irrigation channels in the western rivers.

- If a difference does not fall under these provisions or if a neutral expert feels it does not fall under these provisions, it is deemed a “dispute”.

- In this scenario, the two countries may enter into formal negotiations and even seek mediators. If either approach is unsuccessful, a court of arbitration can be sought to resolve the dispute. But no such court shall be sought while the matter is being dealt with by a neutral expert.

- It should be noted that the last time India and Pakistan consulted a neutral expert was in 2007 when disagreements arose over India’s Baglihar dam project. World Bank-appointed expert and Swiss civil engineer, Professor Raymond Lafitte, gave a green light to India’s overall design for the dam, which was seen as a win for New Delhi.